|

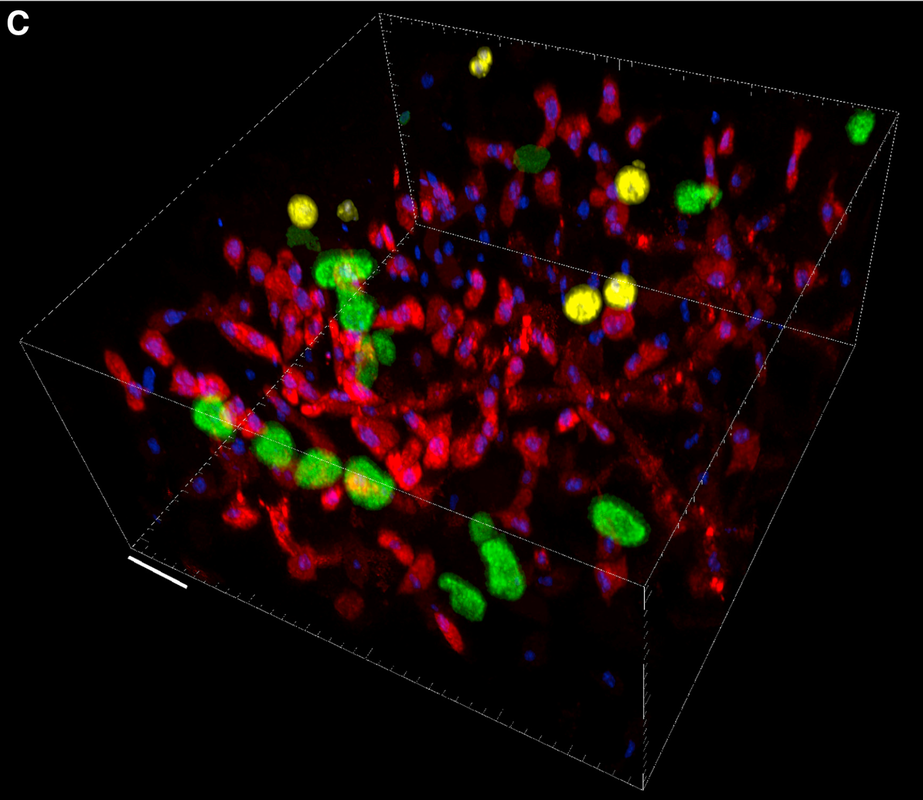

Gorgeous and weird, lichens have pushed the boundaries of our understanding of nature and our way of studying it. EDMONTON–Individual lichens may contain up to three different fungi, according to new research from an international team of researchers. This evidence provides new insight into another recent discovery that showed lichen are made up of more than a single fungus and alga, overturning the prevailing theory of more than 150 years. The new study was a collaboration between the University of Alberta and Uppsala University in Sweden, and led by Veera Tuovinen, a postdoctoral fellow under the supervision of Toby Spribille, assistant professor in UAlberta’s Department of Biological Sciences. A classic example of symbiosis, lichens have long been known to be the result of a mutually beneficial relationship between fungi and algae. “With the microscopy, we could visualize the mosaic of different organisms within the lichen,” said Tuovinen, who completed her PhD at Uppsala University. “We’re realizing that interactions are much more complex than previously thought.” The research team used advanced DNA sequencing to examine the genomes of the wolf lichen, a brilliant chartreuse-yellow lichen that grows on trees across western Canada, the United States, and Europe. While the species is well-studied, the researchers found that, almost regardless of where they were sampled, the wolf lichens contained not one or two fungi, but three. For many, it was a game-changing discovery. “The findings overthrow the two-organism paradigm,” Sarah Watkinson of the University of Oxford told me at the time. “Textbook definitions of lichens may have to be revised.” But some lichenologists objected to that framing, arguing that they’d known since the late 1800s that other fungi were present within lichens. That’s true, Spribille countered, but those fungi had been described in terms that portrayed them as secondary to the main asco-alga symbiosis. To him, it seemed more that the lichens he studied have three core partners. But that might not be the whole story, either. Look on the bark of conifers in the Pacific Northwest, and you will quickly spot wolf lichens—tennis-ball green and highly branched, like some discarded alien nervous system. When Tuovinen looked at these under a microscope, she found a group of fungal cells that were neither ascos nor cyphos. The lichens’ DNA told a similar story: There were fungal genes that didn’t belong to either of the two expected groups. Wolf lichens, it turns out, contain yet another fungus, a basidiomycete called Tremella Previously, scholars had only observed Tremella in galls, or outgrowths, on lichen. “It was thought to be a parasite,” Tuovinen said in the interview. “But we found it in completely normal wolf lichens that don’t have any kinds of bumps.” The scientists labeled each of the fungi with fluorescent tags so they could visualize the composition of the lichen. The images showed Tremella in the outer layer, called the cortex. “With the microscopy, we could visualize the mosaic of different organisms within the lichen,” Tuovinen says in the press release. “We’re realizing that interactions are much more complex than previously thought.” Tremella could be actually a ubiquitous infection of lichens, rather than a member of the symbiosis. Experiments that knock out the fungus could determine its role and whether it’s a critical member of the team. “Without this sort of experimental approach, it seems premature to suggest that Tremella represents a 3rd, 4th, or whatever-th symbiont,” Erin Tripp, a lichen researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder, tells The Atlantic.  This figure reveals the composition of the cortex of a wolf lichen, with Tremella lethariae labeled green, Letharia vulpina (the ascomycete fungus) and algal autofluorescence in red, Cyphobasidium fungus tagged yellow, and cell nuclei in blue. V. TUOVINEN ET AL., CURR BIOL, DOI:10.1016/J.CUB.2018.12.022, 2019 “Our findings from two years ago challenged the long-held view that lichens were made up of a single fungus and alga,” explained Spribille. “This new research complicates the nature of these relationships even further. For one thing, it means that no two lichens necessarily have the same medley of partners.” “What this means in concrete terms to the overall symbiosis is the big question,” added Hanna Johannesson, associate professor at Uppsala University and joint supervisor of the research. “What we are finding now is basically what researchers since the 1800’s would have liked to know–who are the core players, what function do they perform, all the cards on the table.” With the roster of players present in wolf lichens becoming clear, Johannesson and Spribille want to figure out how each member benefits in the give-and-take world of symbiosis. The scientists are particularly interested in the ability of fungi and algae to construct architectural structures from microscopic building blocks. “The fungi and algae that make lichens are doing very interesting things in a confined space,” says Spribille. “Knowing that there might not be any one way to pigeonhole the relationship is very helpful moving forward.” The research was conducted with collaborators from Uppsala University and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, as well as Indiana University in the United States. The paper, “Two basidiomycete fungi in the cortex of wolf lichens,” was published in Current Biology (doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.022). Other article in the subject!: South American lichen found to have 126 different species of fungi.A team of researchers with members from the U.S. and several South American countries has found that a type of lichen that grows in several parts of Central and South America consists of at least 126 species of fungi and possibly as many as 400. As the team notes in their paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, until very recently, the lichen was believed to have just one species of fungus. Lichen is an organism that exists as a partnership between a fungus and photosynthetic partner—it's a photobiont. The main mass of any given lichen generally consists of fungal filaments which host algal cells. In the study in South America, the researchers looked at Dictyonema glabratum, which recently was divided into two separate genera, (Cora and Corella) with initial analysis suggesting 16 distinct species of fungi. D. glabratum (lichen are named after the fungal component) is considered to be ecologically important to South America as it is one among many lichen that fix atmospheric nitrogen into the soil, which makes them natural fertilizers. D. glabratum is generally small, about the size of human fist, and grows in curly masses around other objects, such as tree trunks. In this new effort the researchers expanded on genetic research conducted by other teams that have found that some species of organisms are actually more than one—African elephants are actually two species, for example and there are two distinct species of the Nile crocodile and four species of Killer whales. Curious after the reclassification of D. glabratum, the research team used DNA barcoding and performed phylogenetic analysis on 356 samples and found an astonishing 126 different species of fungi. The team next created a grid map of the range of the lichen, from Central and South America to the Caribbean islands and used it to create a computer model—a simulation from it predicted that it's likely the true number of fungi species in the lichen is close to 452. In retrospect, the lichen may not have been hiding its many species, as evidence offering clues was abundant—they come in several colors, grow on several different surfaces and some even have unique features such as crinkled margins or fine hairs. Researchers have likely missed such clues, the researchers note, due to most studies being conducted using specimens that had been dried and stored for such purposes. Sources: Scienmag The scientist The Atlantic Phys Org

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed